Intervals In Music

In music theory, an interval is a distance between two pitches. This article is a discussion on intervals as understood within music theory. It introduces the concept of what an interval is, as well as the higher level differentiation of semitones, whole tones, and tritones. It also describes the methods of classifying intervals based on their number and quality. Perfect, augmented, diminished, major, and minor intervals are covered. Simple and complex intervals are also examined at the end of the article.

Introduction to Intervals

While music can be thought of as sound and silence arranged in time, we can think of music as being divided into a set of 12 blocks. These blocks are the most basic elements of music and are used to construct all the higher-level structures used in music theory.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|

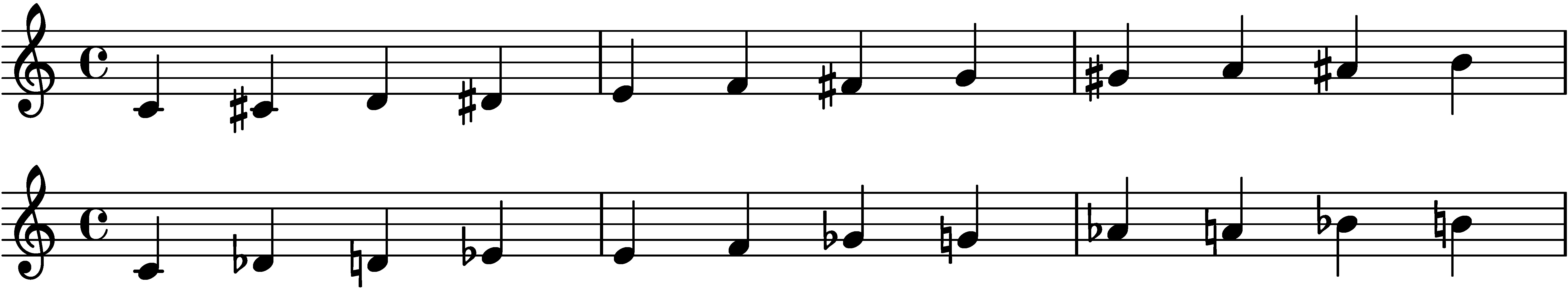

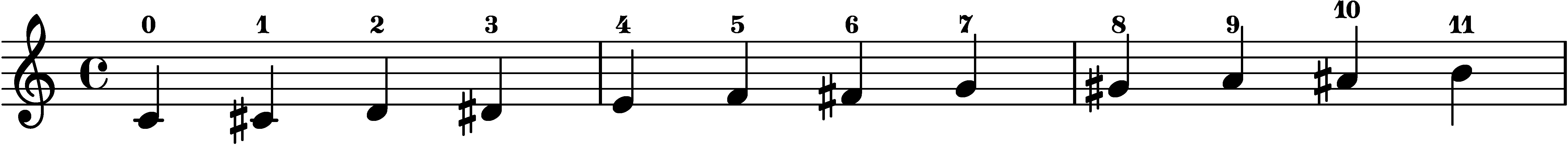

If we were to assign pitch values to this set, the chromatic scale is created. This is a scale with twelve tones, in which each member of the set is a semitone above its predecessor. In Western music, this scale spans all the available tones.

Chromatic Scale:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B |

| Db | Eb | Gb | Ab | Bb |

Semitones, Whole Tones, and Tritones

The distance between each block is called a semitone, the distance between two blocks, which spans two semitones, is called a whole tone, and the distance between three whole tones, or six semitones, is called a tritone.

Each interval is constructed with a certain number of semitones, but there can be multiple names for an interval with the same semitone number. There are several rules for classifying intervals in addition to the semitone number, which will be discussed below.

Pitch and Pitch Class

Before going further in our discussion of intervals, it is important to understand the differences between pitch and pitch class. The former is a particular instance of the general concept of the latter. For example, the pitch class is the set of all s, while A4 (at 440Hz) is a distinct pitch.

Pitch classes are often expressed in integer notation, which is simply a zero-indexed set of numbers: . The following standard notation chromatic scale is annotated with the pitch classes each note is an instance of.

Each of the tables in this article will have a column that corresponds to the pitch class of the note in question, expressed in both integer notation and with the standard letter name convention. This is especially important in the discussion of compound intervals, where thinking in terms of the simple interval each compound interval corresponds to is important.

Classifying Intervals

The two primary ways in which intervals are classified in Western music are by number and quality.

Interval Number

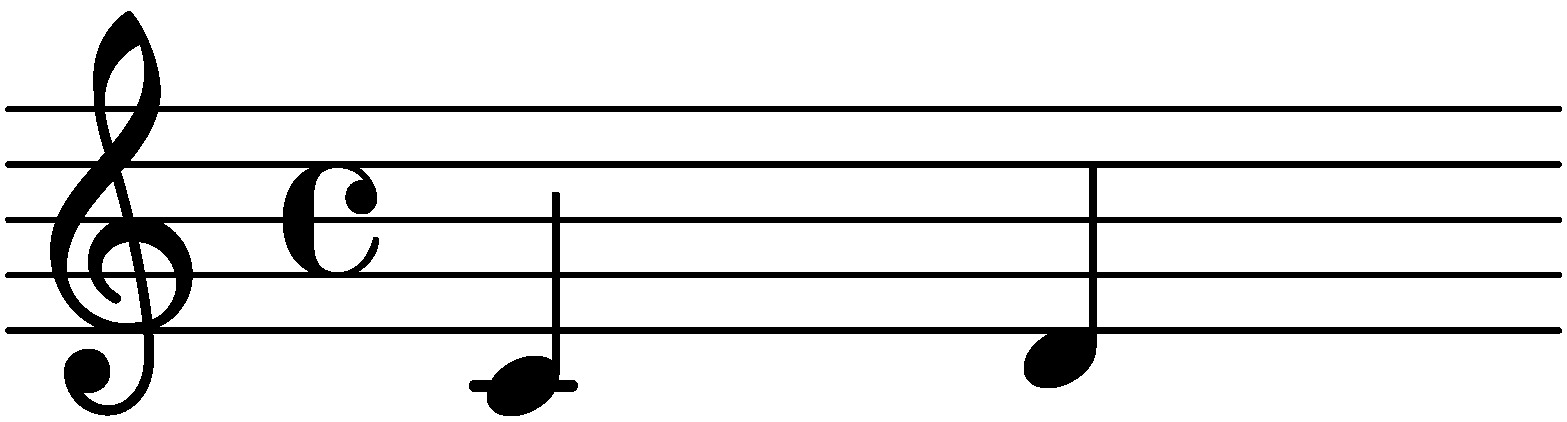

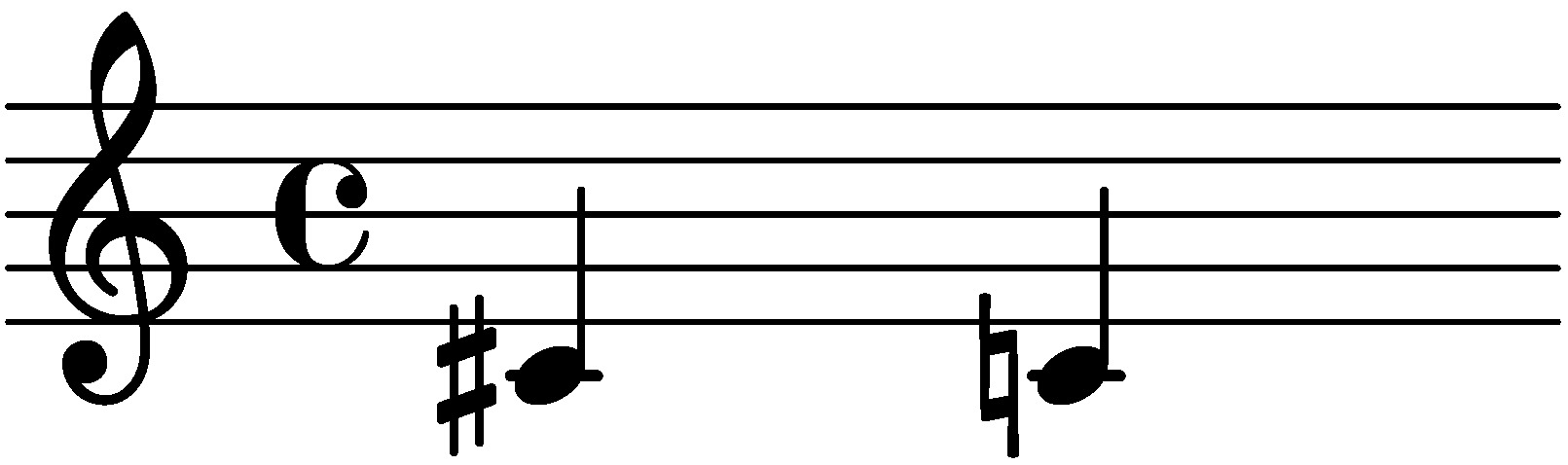

The number of an interval has to do with the number of letter names or the number of unique staff positions it contains.

For example, the interval of C--D is a second because it has two note letter names (C and D), and contains two unique staff positions.

This can be expressed with our table of blocks as follows:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | C# | D | D# |

The C# and C♮ in this table do not have a unique interval number, although they do have a unique semitone number. The interval number has to do with unique letter names, which in this case are both C, and staff positions, which are:

This is expressed in tabular fashion as follows, with Block Number being the initial set of 12 blocks, Note Name being the name of the note, with the enharmonic equivalent if applicable, and Interval Number being the interval number of the note based on the definition above.

| Block Number | Note Name | Interval Number |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | C | 1 |

| 1 | C#/Db | 2 |

| 2 | D | 2 |

| 3 | D#/Eb | 3 |

| 4 | E | 3 |

| 5 | F | 4 |

| 6 | F#/Gb | 4 or 5 |

| 7 | G | 5 |

| 8 | G#/Ab | 5 or 6 |

| 9 | A | 6 |

| 10 | A#/Bb | 7 |

| 11 | B | 7 |

| 12 | C | 8 |

There are a couple of odd things to note about this table. First, the last note name in the table is the same as the first. This is our octave, which is a unique instance of the pitch class C. The second item to note is that for the enharmonic equivalents and , which have a semitone number of 6 and 8, respectively, can have an interval number of either 4 or 5. This is due to the unique properties that these two intervals have when found in a diatonic context.

Interval Quality

The quality of an interval can be one of the set perfect, major, minor, augmented, and diminished.

Perfect Intervals

A perfect interval is one that is considered consonant in traditional Western classical theory. The evolution of music has led to a greater number of intervals considered consonant, and most modern musicians and composers would not consider the perfect intervals to be the only valid consonant intervals to use in improvisation or composition. However, these are typically considered the most consonant intervals.

The perfect intervals are:

| Number of Semitones | Name |

|---|---|

| 0 | Perfect Unison |

| 5 | Perfect Fourth |

| 7 | Perfect Fifth |

| 12 | Perfect Octave |

A possible reason as to why the unison, octave, and fifth sound so pleasant to humans is that they are higher in their position on the overtone series. The overtone series, or harmonic series, is the sequence of frequencies that are multiples of the fundamental, or the starting simple wave. As an example of this, take the simple wave of 440 Hz (an A4). The first harmonic is 440 Hz, the second harmonic is 880 Hz (an A5), the third harmonic is at 1320 Hz (an E6), and the fourth is at 1760 Hz (an A6). In the first four members of the series, we have a unison, an octave, a fifth (an octave above), and another octave. This creates a strong sense that the unison, octave, and fifth sound pleasant together. While a full discussion of the harmonic series is well outside of the scope of this article, the harmonic series is an interesting way to think about interval consonances and dissonances.

Augmented and Diminished Intervals

Perfect intervals, when modified, are either augmented or diminished.

Major and Minor Intervals

| Number of Semitones | Major/Minor/Perfect | Diminished/Augmented |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Perfect Unison | Diminished Second |

| 1 | Minor Second | Augmented Unison |

| 2 | Major Second | Third |

| 3 | Minor Third | Augmented Second |

| 4 | Major Third | Fourth |

| 5 | Perfect Fourth | Augmented Third |

| 6 | Diminished Fifth / Augmented Fourth | |

| 7 | Perfect Fifth | Diminished Sixth |

| 8 | Minor Sixth | Augmented Fifth |

| 9 | Major Sixth | Diminished Seventh |

| 10 | Minor Seventh | Augmented Sixth |

| 11 | Major Seventh | Diminished Octave |

| 12 | Perfect Octave | Augmented Seventh |

Simple Intervals

Simple intervals are intervals within a single octave. The following table lists the simple intervals.

| Name | Number of Semitones | Pitch Class | Pitch Class Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect Unison | 0 | 0 | C |

| Minor Second | 1 | 1 | C#/Db |

| Major Second | 2 | 2 | D |

| Minor Third | 3 | 3 | D#/Eb |

| Major Third | 4 | 4 | E |

| Perfect Fourth | 5 | 5 | F |

| Augmented Fourth / Diminished Fifth | 6 | 6 | F#/Gb |

| Perfect Fifth | 7 | 7 | G |

| Minor Sixth | 8 | 8 | G#/Ab |

| Major Sixth | 9 | 9 | A |

| Minor Seventh | 10 | 10 | A#/Bb |

| Major Seventh | 11 | 11 | B |

| Perfect Octave | 12 | 0 | C |

Compound Intervals

Compound intervals are intervals spanning a distance greater than one octave. The number of semitones from the root note is expressed in the following table, as well as the pitch class. If you compare this table with the simple interval table, it is clear that the pitch classes are the same after passing the octave. This means that a ninth is just a second, an eleventh is just a fourth, and a thirteenth is just a sixth, all an octave up. The following table lists the compound intervals.

| Name | Number of Semitones | Simple Interval | Pitch Class | Pitch Class Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor Ninth | 13 | Minor Second | 1 | C#/Db |

| Major Ninth | 14 | Major Second | 2 | D |

| Minor Tenth | 15 | Minor Third | 3 | D#/Eb |

| Major Tenth | 16 | Major Third | 4 | E |

| Perfect Eleventh | 17 | Perfect Fourth | 5 | F |

| Augmented Eleventh | 18 | Augmented Fourth | 6 | F#/Gb |

| Perfect Twelfth | 19 | Perfect Fifth | 7 | G |

| Minor Thirteenth | 20 | Minor Sixth | 8 | G#/Ab |

| Major Thirteenth | 21 | Major Sixth | 9 | A |

| Minor Fourteenth | 22 | Minor Seventh | 10 | A#/Bb |

| Major Fourteenth | 23 | Major Seventh | 11 | B |

| Double Octave | 24 | Perfect Octave | 0 | C |

Hopefully, this article helped with your understanding of intervals and the role they play in music. Other posts about music theory can be found in blog.